Why does one person become an addict and another person does not?

The vulnerability/susceptibility to addiction is one of the most important questions in the addiction field and also one of most difficult to answer. Is it genetics, the environment, or the addictive power of the drug itself? Spoiler alert: the answer is all three! But rather than trying to explain the answer in mere blog post (which is impossible), I think it’s better to tackle different aspects of the question in multiple posts (well, I probably could do it in one but I’m scientist: I would be a doing a disservice to you and to myself if I didn’t do a thorough job). This is the first post in this series.

Over the years, a lot of research has been done that has been able to show that stress can contribute to why one person becomes an addict and why another person does not. But how do we know that stress is important? And what is “stress” anyways? Let’s get our information straight from the horse’s mouth so to speak: a review of a few research papers that look at this question.

What is Stress?

Stress is one of those terms that is used often but may not be well understood. At one point or another we’ve all described our day as “stressful” and we all understand what this means but just take a moment and try to describe what “stressful” means in words that apply to ALL “stressful” situations. It’s tough, right? That’s because stress can mean any number of things in a number of different contexts.

In biology, we have a specific definition of stress: a response (usually immediate and automatic) to an environmental condition or factor, a stimulus, or other type of challenge. The body has several systems in place that mediate the stress response. For example, you probably have heard of “fight-or-flight”, which is one of the body’s stress responses.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis

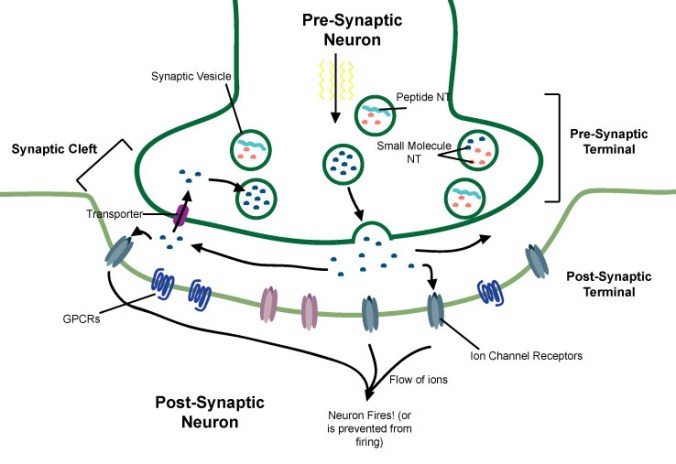

Another of the key components of the body’s response to stress is the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. See the diagram. The HPA axis is hormonal system that involves chemical communications between several organs.

- First, something happens that requires the body to respond to it, this could be sudden change in temperature, or an attack by an aggressor, or some other challenge. This factor is called a stressor.

- Second, the stressor causes the hypothalamus, a region of the brain that controls many of the body’s functions, to release a small protein molecule called corticotropin releasing factor or hormone (CRF or CRH)

- Third, CRF acts on the anterior pituitary gland, a small organ that secretes many different hormones. CRF stimulates the pituitary to release another small protein called adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH then enters the blood stream.

- Fourth, ACTH travel through the bloodstream until it finds its way to the adrenal glands, small organs that are located on top of the kidneys.

- Finally, ACTH causes the adrenal gland to release cortisol (corticosterone in rodents), the “stress hormone.” Cortisol has many effects on many different organs throughout the body. Cortisol can also act on the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland themselves in order to inhibit their release and turn the HPA axis “off” until the next stressor. This is called a negative feedback loop.

Note: This is of course, a simplified model and there is a whole field of research devoted to working out the precise molecular mechanisms that regulate the HPA axis and how it responds to many different kinds of stressors.

Stress plays an important role in addiction. Stressors can make a drug seem more appetizing or even make it even feel better (more pleasurable). Anecdotally, after a stressful day, did you ever feel like you really needed a drink? Or, for the current and/or former smokers, how a cigarette was especially satisfying after a particularly jarring event? There’s a neurobiological reason for that feeling!

How do we know stress is important in addiction?

We are going to examine a few research papers that span over two decades (this discussion will be split over two posts). Each paper will reveal a little piece of the puzzle about why stress makes drugs more addictive. However, a Google Scholar search for “stress and addiction” gives you 527,000 hits! Basically, I chose these ones because they are easy to explain and, more or less, fit together in a sequence. Also, they all use one or more of the techniques that I described in my last post: The Scientist’s Toolbox: Techniques in Addiction Research, Part 1. I encourage you to read it before proceeding.

As we go through, try to keep the question we are trying to answer at the back or your mind: Does exposure to stress make it easier to become an addict and, if so, how does it do this? But this is a big question so it’s broken down into little pieces that each paper will try to answer. By the end of the second post, all the little pieces should add up to the bigger story.

Paper #1

Paper #1

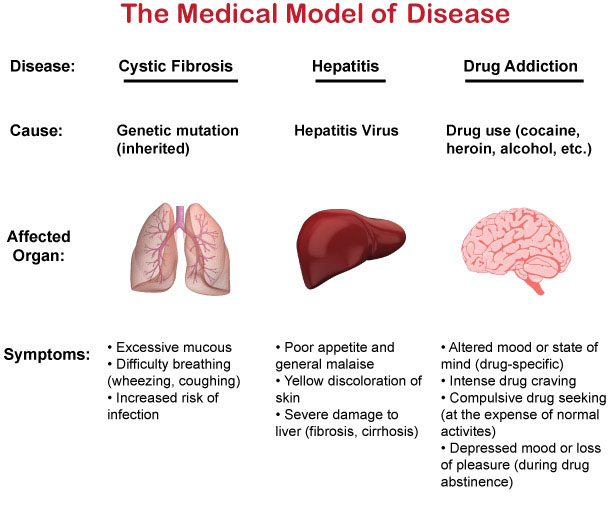

Both of the papers we’ll go over today look at what effect stress has on the behaviors of rats exposed to psychostimulants, either amphetamine or cocaine.

As I described in The Scientist’s Toolbox, psychostimulants cause an animal to move around more, and subsequent doses, over a period of a few days, increase that movement. Recall that this phenomenon is called locomotor sensitization.

Figure 1: Behavioral sensitization to amphetamine. Locomotor activity test (left panel) and self-administration (right panel).

In the first paper, rats are given 4 injections of amphetamine, one injection of amphetamine every three days and, sure enough, after the fourth injection exhibit greater locomotor activity; these rats are exhibiting locomotor sensitization to amphetamines. These results are shown in the left panel of Figure 1: black circles (4th dose of amphetamine) vs white circles (1st dose). Similarly, rats were given the same regimen of injections and 24hrs after the fourth injection self-administration of amphetamine was tested. As show in the right panel of Figure 1, only animals that were previously exposed to amphetamine (black circles) compared to saline-exposed rats (white triangles) self-administered amphetamine (nose-poked in order to receive drug infusions).

For the next experiment, there are two groups of rats: one group is exposed to stress and other is not. The type of stressor used in these experiments is called tail-pinch and it is exactly what it sounds like: a device is set to deliver a quick squeeze to the rat’s tail. This causes just a mild amount of pain and is very unexpected to the animals, thus it “stresses them out”. This means, as shown in other studies, that tail-pinch activates the HPA axis (increased cortisol secretion). In this experiment, no apparatus is used so instead the rats are placed in a bowl one at a time and then the scientist pinches the tail using forceps (tweezers).

Figure 2: Impact of stress on the behavioral effects of amphetamine. Locomotor activity (left panel) and self-administration (right panel).

Each animal in the stress group is exposed to 1min of tail pinch, 4times/day for 15days. This represents a chronic stress. The non-stress group rats are also placed in the bowl but no tail-pinch is applied. This is important to make sure that simply being handled or being put in the bowl is not having an effect. This non-stress group is an essential part of the experiment because it allows us to compare the effects of the stress test to animals that did not receive the test. It is called a control group. Controls are necessary for every experiment so that the scientist can make a useful comparison and allows him/her to interpret the experimental results.

Back to the experiment: 24hrs after the last tail pinch, both groups of animals are give an injection of amphetamine and their locomotor activity is measured. As you can see in the left panel of Figure 2, amphetamine caused greater movement in the animals that were stressed (black triangles) compared to the non-stressed control group (white triangles). This means, the ability of amphetamine to affect the animal’s movement was enhanced by stress.

In the second part of this experiment, the same stress exposure procedure is done but then the animals undergo a self-administration experiment (if you’re interested in the details, the catheter surgeries are completed before the stress exposure is started). As shown in the right panel of Figure 2, the stress group (black triangles) successfully acquired self-administration, meaning they gradually self-administered more and more amphetamine every day of the experiment. This behavior is similar to how human addiction begins, escalation in the amount of drug taken each time. Interestingly, the non-stress control group (white triangles) self-administered amphetamine for the first two days but gradually stopped and didn’t really seem interested in receiving the drug by day 5.

Figure 3: Comparison of prior exposure to drug (sensitization) to stress: impact on the behavioral effects of amphetamine. Locomotor activity (left panel) and self-administration (right panel).

In Figure 3 the authors of this study compared the effect of prior exposure (sensitization) to stress for both the locomotor and self-administration experiments. They did this by dividing the experimental data by the control data (this is called normalization). There appears to be no difference between prior exposure and stress on locomotor activity and self-administration.

The authors conclude that stress is as potent as prior exposure to enhance the properties of the drug; stress exposure may be a significant factor why some people become addicted while others do not.

So very cool, it looks like stress can cause rats to want to self-administer more amphetamine and enhance the physical effects of the drug. Many other studies have found similar effects of stress. Let’s take a look at one paper that uses a different stress and a different drug.

Paper #2

Paper #2

In this study, the drug studied is the psychostimulant cocaine and the stressor is social stress. There are many variations of the procedure used for social stress but many are similar. In this paper, the rat to be stressed (the intruder) is placed in the home cage of a different rat (the aggressor). Because rats are territorial, this provokes the aggressor to attack the intruder. The intruder is left in the aggressor’s cage until it is bitten 10 times by the aggressor. The intruder rat is then placed in a mesh cage and put back in the home cage of the aggressor for a period of time. This way the intruder can still see and smell its attacker but can’t be physically attacked. This is repeated for several days. Social stress has been shown to be a very potent stressor, probably more so than tail pinch.

Note: The other study looked only at males but this study is interested in both males and females but for what we are interested in, this is a minor detail.

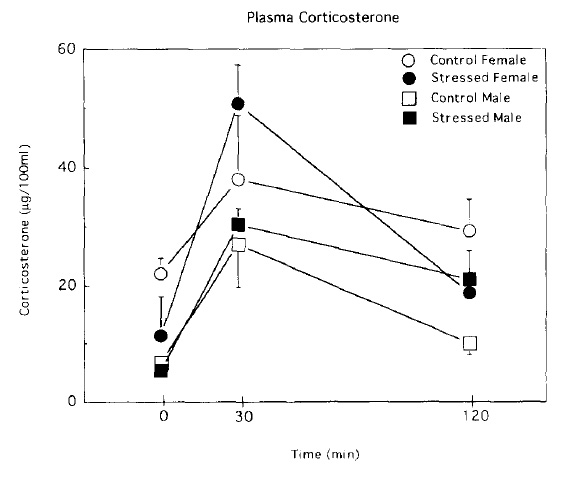

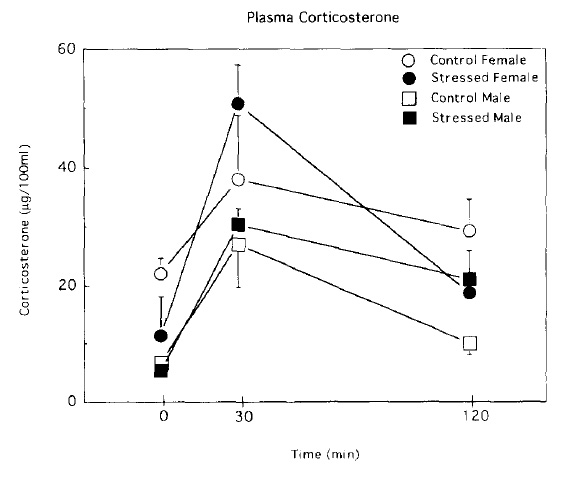

Figure 1: Corticosterone levels in a novel environment in stresses and un-stressed male and female rats

First, activity of the HPA axis is measured by looking at corticosterone levels (this it the rodent equivalent of cortisol) when exposed to a novel environment (a novel environment is itself a type of mild stress). As you can see in Figure 1, rats that were previously exposed to social stress (black symbols) released higher amounts of coricosterone when placed in the novel environment compared to their unstressed counterparts (white symbols). This means the social stress has resulted in activation of the rat’s stress response, the HPA axis. Interestingly, female rats seemed to have a greater stress response overall.

Figure 2: The effect of social stress on cocaine self-administration.

Next, the effect of social stress on self-administration of cocaine is tested. As we saw with tail pinch stress and amphetamine, social stress caused an enhanced acquisition of cocaine self-administration whereas unstressed animals did not acquire cocaine self-administration. These data are presented in Figure 2, stressed rats (black symbols) and unstressed rats (white symbols).

In this paper, the authors also conclude that social stress—and activation of the HPA axis—makes it easier for a rat to acquire to cocaine self-administration; stress makes the rat want to self-administer cocaine.

To summarize: these studies have found that two different types of stress have a similar effect on two different kinds of drugs. The first study found that tail-pinch stress increases the amount of locomotor activity induced by amphetamine. This stress also increases the amount of drug that the animals will self-administer. The second paper found that a different kind of stress, social stress, caused an activation of the HPA axis and had the same effect on cocaine self-administration: animals exposed to stress acquired self-administration behavior.

Based on the self-administration data, we conclude that stress caused the drugs to have a greater reinforcing effect. This is measure of the amount of pleasure the animals get from the drug. Therefore, we interpret that the stress made the drugs more pleasurable to the animals because they wanted to self-administer more drug.

However, there are some caveats that need to be briefly discussed. Both of these studies only looked at short term self-administration experiments (5 days) and both used relatively low doses. Many studies have found the rats and mice will self-administer cocaine and amphetamine regardless of whether they were exposed to stress or not. Nevertheless, these two papers are examples of how exposure to stress can cause a drug to be more addictive (technically, more reinforcing).

Next, we’ll look at some more stress studies that try to identify the molecular mechanisms—what stress is actually doing to the brain—of stress and addiction.

If you made it this far, thanks so much for sticking with it!

Just as a last thought: both of these are old papers, from the 90s and both are not very extensive (compared to today). This may sound incredible but it’s just an example of how difficult and time consuming science really is!

Thanks for reading 🙂